SECTION ONE

The Pure Cambridge Edition of the King James Bible has existed

a long time, for many decades, and is therefore very fitting to be considered

as a genuine and standard representation of the King James Bible.

In his lesson #273 on the history of the King James Bible text, Bryan Ross continued ignoring the actual history of the Pure Cambridge Edition, but rather just concentrated his study on my beliefs. He obviously has very different views in relation to Pentecostalism, so I think that’s a lot of the reason why he is pushing so far into this area.

Remember, that I am clear that I have beliefs, and am upfront about them. Remember also that the King James Bible is in the hands of the Body of Christ, so this is not my property. And also, the Pure Cambridge Edition existed for a long time before I was ever born, so again, it is commendable as a standard, even if Ross has real problems with my Pentecostal beliefs. (One Pentecostal can have issues with other Pentecostals because there’s a variety of them!)

I have brought up a variety of reasons for the King James Bible and the Pure Cambridge Edition, which I have made from my perspective of history, doctrine, etc. These are to make sure there is consistency from my view, but there are specific points that I’ve made which are like passing facts but not that I major on.

While I believe that Pentecostalism is correct, my point is for people to have the King James Bible, and that’s the emphasis I’ve taken, which is evident in everything I’ve written. However, for obvious reasons Bryan Ross has concentrated on those areas (e.g. a comet), and it seems he is trying to make out things too far.

Now, since the Scripture is the basis for doctrine, from my

point of view, I would want to see how the Scripture would relate to it, and

specifically, being Pentecostal, I’d want to make sure that proper Pentecostal

doctrines match the King James Bible.

To be clear, if the Bible itself is the basis of doctrine,

and the PCE an “instance” of the Bible, then it has not been Pentecostal

doctrine that made me select the PCE. If, in any way, Ross tries to say this,

he would be completely wrong. I am actually arguing that if we start from the

KJB, and a proper presentation of it, that we should align our doctrine to it.

I have sought to understand right doctrine from a right presentation of

Scripture.

The problem for Bryan Ross is that I don’t think he is starting from the KJB as the actual foundation to his doctrine. I suspect in some areas he is misinterpreting Scripture by applying certain beliefs onto Scripture, but I don’t want to talk about that, because that’s something that can be argued in general for a lot of Christians. Instead, I want to ask whether or not Bryan Ross is actually appealing ultimately to the KJB as its own authority as the basis of his doctrines, or whether he is really going to the original languages as his ultimate appeal. (That’s also an issue with his grammatical-historical interpretative method.)

So, it is only since the PCE that I have sought this idea of

saying that pure doctrines are going to be built on having the pure word in

practice. I did not arbitrarily select the PCE because it somehow was going to

give me a biased outcome, I look to it on the basis of Providence, etc. The

outcome is whether or not the Body of Christ can come to the KJB and to the

PCE, and that we all build our doctrine on the same thing. I’m saying it is the

work of God, if we judge doctrine by the PCE, we will see whether

Pentecostalism, Trinitarianism, etc. is right. I think they are, but I think

the issue now will be upon accepting the PCE as the basis, whether people will

keep to the grammatical-historical interpretation method that is not even

KJB-centric, or whether we actually have an English-scripture-exclusivity in

our doctrine, and then interpret with one mind to have a unified body of Christ

with correct doctrine.

My “real” belief is not merely about the PCE, but is about

this verse:

“Till we all come in the unity of the faith, and of the

knowledge of the Son of God, unto a perfect man, unto the measure of the

stature of the fulness of Christ: That we henceforth be no

more children, tossed to and fro, and carried about with every wind of

doctrine, by the sleight of men, and cunning craftiness, whereby they lie in

wait to deceive;” (Eph. 4:13, 14).

Logically, if Christians have the same set of words, and

interpret by the true Holy Ghost, then we will come to the unified Body of

Christ.

I believe in moving towards that. And with ancillary

doctrines being Wesley’s and Finney’s Christian Perfection, and Word of Faith’s

controversial doctrine about being sons of God, then just how far could things

go before the rapture?

It is a faith position because sight says, “people are

squabbling about whether there even is a correct edition of the KJB” let alone

the millions of other squabbles that a person might regard. I know what I am

saying may seem very extreme now but I think it is a good extreme for us all:

basically we have to ignore everything and believe Ephesians 4:13, 14.

“Who is blind, but my servant? or deaf, as my messenger that

I sent? who is blind as he that is perfect, and blind as the Lord’s servant?

Seeing many things, but thou observest not; opening the ears, but he heareth

not. The Lord is well pleased for his righteousness’ sake; he will magnify the

law, and make it honourable.” (Isaiah 42:19–21).

SECTION TWO

In my original longwinded analytical approach on several editorial differences between the Pure Cambridge Edition and other editions, one of the fields of study I suggest is to measure editorial differences on doctrinal bases.

Now, remember, this is long after looking at the 1611

Edition, and at various historical editorial editions, like 1769, and the

context, and so on. After all that, then to think about doctrinal implications

of editorial differences.

In my draftings of my “Guide to the PCE”, I have an area

(which being a draft is still subject to editing) which Bryan Ross quoted. It

is where I make some comments about the lower case versus capital form of

“Spirit” at Matthew 4:1 and Mark 1:12.

I acknowledge that area needs to be edited for clarity, but Bryan Ross is trying to make something more than what I am meaning.

First, that various older KJBs have the word “spirit” in

lower case at Matthew 4:1 and/or Mark 1:12 when the parallel passage in Luke

shows it is the Holy Ghost, meaning that we know it should be the “Spirit”.

Second, let me say that this has been perfectly legitimate

historically as far as plenty of Christians using Bibles that have had that

variation, but only when pressed on very exacting doctrinal grounds could we

say that this is inaccurate. I do not think anyone has been seriously or

doctrinally led astray because Bibles got it wrong back in the 18th

and 19th centuries on this point.

Third, because of the potential to lead people astray,

especially in context of the Pure Cambridge Edition being known and

established, but in general, then obviously it would start to become

problematic in a real sense to reject the “Spirit” capital rendering. Only upon

insisting upon rejecting that the Holy Ghost actually is being meant would

amount to blasphemy.

Rhetorically, one can ask the question, are you insisting on

a lower case “spirit” at Matthew and Mark there to deny the Holy Ghost

specifically? If so, such a motivation would lead into error or even blasphemy,

surely. That is, as this issue becomes more aware, and people begin to take the

printing of the KJB seriously, and editorially people refuse to conform to

“Spirit” there, or start to argue and support “spirit” in Matthew and Mark

there, then I think they would have to be pushing for something erroneous.

Further, if by accident, based on the historical times of

wrong printings in some editions, people concluded that it meant something

other than or against the Holy Ghost, I would think this a problem to be

avoided by having a standard edition.

After all, both Cambridge in other editions and some Oxford editions themselves have moved to “Spirit” in Matthew and Mark, so obviously there has been a fair bit of agreement on this point. It is therefore not a singular opinion of mine, but it was such an issue that even other publishers have made the change before I was born!

So it’s pretty clear that Bryan Ross is making too much of

the matter, though I can say that I hope to clarify the issue by finishing the

draft one day, so as to better express the information, and also so that people

like Bryan Ross don’t try to say that I am saying “spirit” historically was a

specific blasphemy, when we know that variation has existed in how the word

“spirit” or “Spirit” has been capitalised or not.

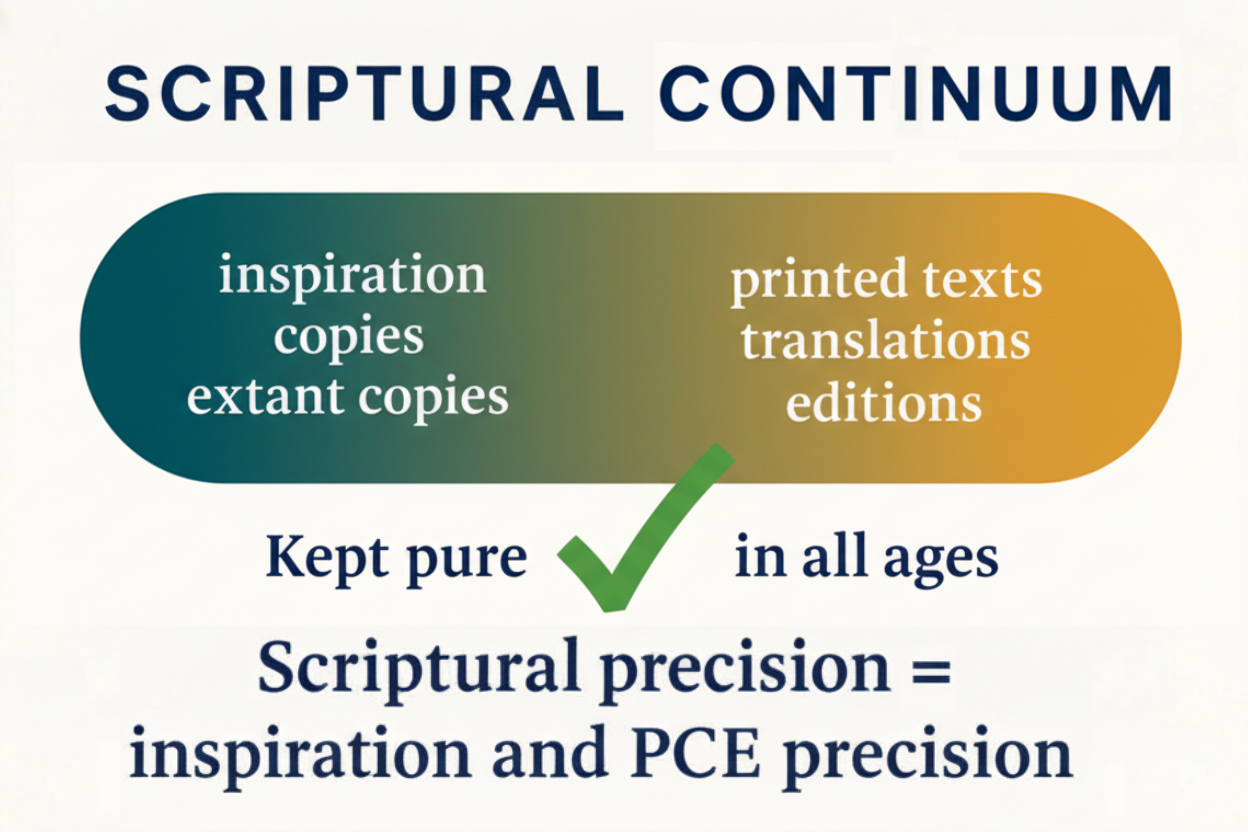

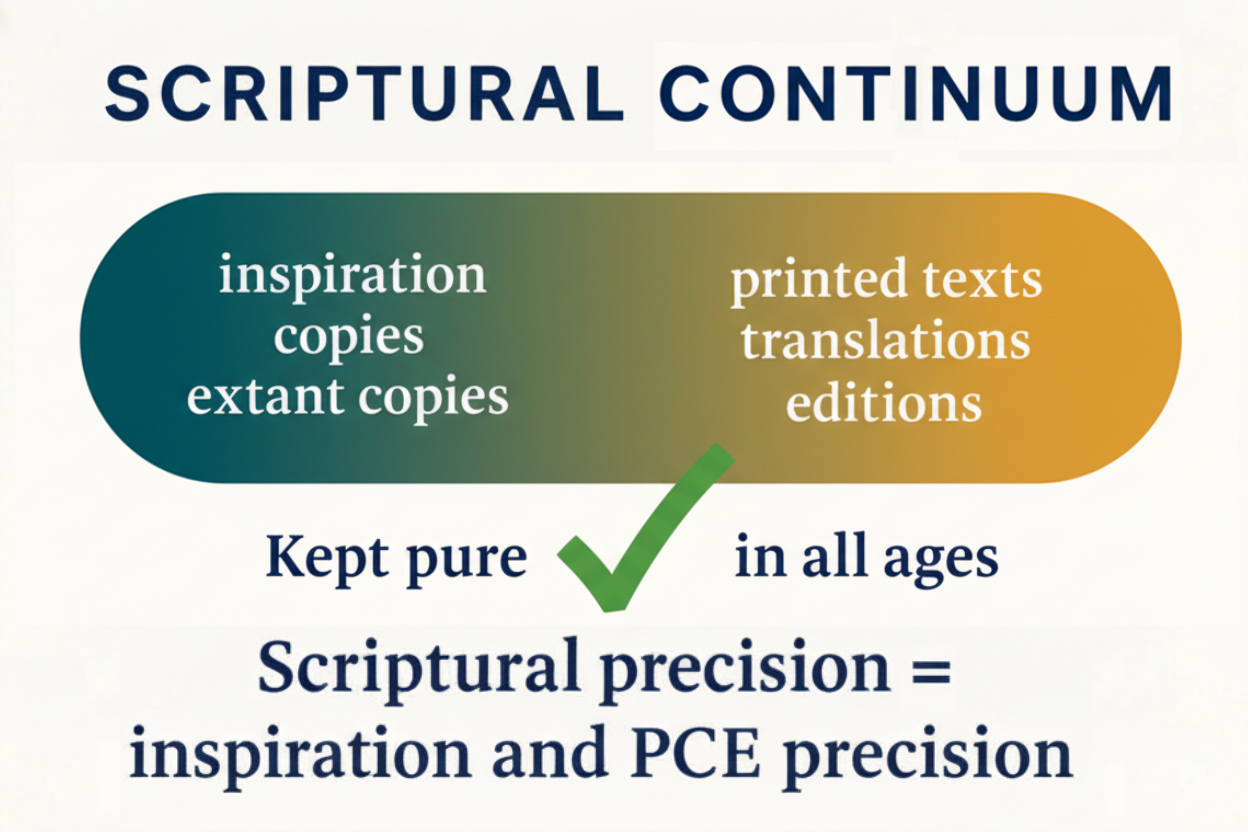

Bryan Ross is trying to peg me into a “verbatim

identicality” corner for his own rhetorical interests, when I clearly have

already explained that having the PURE text and translation of 1611 is a

separate matter to having pure editing, orthography and printing/typesetting.

Ross is unfairly conflating these matters.

So, Ross cannot be trusted to present my Pentecostal views

quite fairly as he has a bias against those views, though he did have plenty of

quotes from me, if when taken themselves, do indicate my views.

I do believe in a range of views outside of the usual label

of “Pentecostal”. I personally can get along with people from a variety of

denominations which might be usually “non-Pentecostal”. I think the KJB is for

all Christians, and believe that there is a conformity to proper doctrine that

would be happening only by God, because with man that would seem impossible.

Finally, I want to make it very clear that everyone who is

born again has the Holy Ghost, which is the Spirit of God. I’d like all

believers to use the KJB, and specifically, to use the PCE.

Proper Pentecostalism teaches that beyond being born again

is the invitation (really the command) that Christians should have a full

baptism in the Holy Ghost which does have a specific evidence of speaking in

tongues.

And you know, I could use an Oxford Edition to teach that. I

could use an Oxford Edition the doctrine of the Trinity, the doctrine of the

Pre-Tribulation Rapture, etc. So, I think Bryan Ross’ stretched conclusions

need to be brought into check.

SECTION THREE

I want to continue to clarify some things so as to answer

Ross’ critiques that have been raised regarding Pentecostal theology, doctrinal

reasoning and the PCE.

First, to answer Ross’ claim that my acceptance of the PCE

was driven by Pentecostal theology. This is not the case. My initial

recognition of the PCE as a standard representation of the King James Bible

came by Providential reasoning and historical examination, not from doctrinal

presuppositions. The PCE existed for many decades before I was born, and its

existence, editorial consistency and alignment with historical printings were

primary factors in my evaluation. Sound theology is relevant only after this

assessment, as a confirmatory lens, helping to understand how certain editorial

readings — like “spirit” or “Spirit” — relate to broader Christian doctrine.

Yes, my theology includes Pentecostalism, but it did not dictate my acceptance

of the PCE.

Second, regarding doctrine’s role: yes, doctrinal reasoning functions normatively at decisive points, but always after historical, textual and providential analysis. For me personally, Pentecostal theology is a presupposed truth, but my concern is not to impose a theological outcome on the text. In fact, the opposite is the case. I have approached the PCE as dictating doctrine, and in a consequential way explored how the PCE naturally aligns with proper doctrine as a whole. (And, yes, I think there is proper Pentecostal doctrine as part of full proper doctrine.) My approach remains consistent: Providence and textual reality come first, doctrinal observations came second.

Third, about the finality of God’s words being manifested definitively:

the authority and correctness of the PCE are both theologically and

historically grounded. Theology provides the presuppositional lens of God’s

providence, while history and the observable reality of PCE printings available

to the early 2000s provide the factual substrate. This creates a

self-authenticating standard: the PCE demonstrates internal consistency,

historical continuity and practical usability in the Body of Christ. Authority

to treat the PCE as final is exercised through discernment informed by these

factors, not by a reproducible or mechanical method alone. The modern world and

Enlightenment philosophy tend toward revision because of uniformitarian tendencies

(all things continue as they have) which is something which the PCE’s stability

and finality answers, based on a view that God is outworking to very specific

ends.

In regards to the “Spirit/spirit” issues in Matthew 4:1,

Mark 1:12, Acts 11:12, Acts 11:28 and 1 John 5:8, these cases illustrate how

textual variation interacts with downstream doctrine. Historically, earlier

editions quite often printed “spirit” in lowercase, and legitimate practice

survives in many places where simplistic assumptions might demand “Spirit”

capital. In places the “Spirit” capital was made, it was obviously for good

reasons.

In fact, I think that the reasons for the 1769’s “spirit” at

Matthew 4:1 to the modern day “Spirit” capital are entirely legitimate, and can

easily be, by common sense, demonstrated on conference and doctrinal grounds.

And to fight that change by strong resistance and so on would be a most grave

error, because at some point it would become a blasphemous reason why it is

being resisted I would think.

So, it would seem strange for Cambridge to, on no doctrinal or other good grounds, make the decision to make 1 John 5:8 “Spirit” capital when it has stood as “spirit” lower case since 1629 in normal Cambridge printings. Blayney had “spirit” too, and do many other sources. So then why was this suddenly an “embarrassment”? On what grounds exactly is it an embarrassment?

Weirdly, Bryan Ross, who basically tries to argue that there is only “verbal equivalence” yet hypocritically is ready to wave about an 1985 letter from Cambridge as some sort of victory … I though he was prepared to accept all normal editorial variations in his libertarian approach?

Yes, I say “normal” in a contemporary sense, but the are not all right.

Anyway, my investigation into these readings was first

historical and textual, noting how older Cambridge and Oxford editions rendered

the words. Only later, as a clarifying measure, did I explore what the

doctrinal implications could be of these in different editions, and obviously

my doctrinal reasoning includes a Pentecostal understanding. This demonstrates

that textual reality is primary, and doctrinal interpretation comes as a

secondary lens to confirm or clarify meaning, not to create the standard

itself.

Accepting the standard is a doctrine in itself, not

Pentecostal in a traditional sense, but a Fundamentalist, Providentialist and Puritan-derived.

And since my idea of the authority of theology flows from

starting from the PCE as a standard, I can say that specific textual questions,

such as “Spirit” versus “spirit,” were assessed first by historical and textual

reality, and secondarily by doctrinal clarity, ensuring the PCE both reflects

the historic text and aligns with proper theological understanding. I think a

lot more theological study needs to be done, and it’s there for the entire Body

of Christ to look at and study.

The PCE is not some textual curiosity but is a practical,

providential and spiritually validated standard for the King James Bible in

English, available to all believers, and a basis upon which Christians may

rightly interpret doctrine and pursue unity.

And for the record, I did not have a checklist of Pentecostal doctrines and then check editions to make sure I could find a most confirmatory edition of all edition options.

I did not know in 2001 or 2002 that the 1769 Edition had “spirit”

lower case at 1 John 5:8.

I really hope that the disagreement that Ross has with me is

not my faith-based providential finality versus a historically open-ended

textual stewardship position, because I know exactly where the modernists sit

on that spectrum.